Early this month, the Chinese-only website of Zhenhua Data Information Technology Co, the company monitoring foreign targets, was pulled down soon after The Indian Express approached it for comments. What kind of data has it collected on the targets, what does it mean when it says it’s engaged in hybrid warfare, what’s the cause for concern? Here are the key questions answered:

What does Zhenhua Data do?

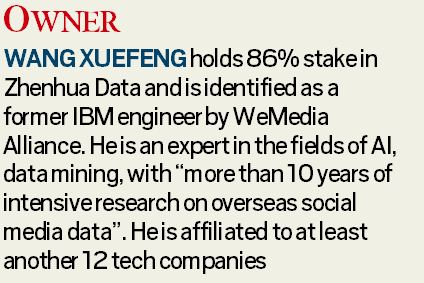

It targets individuals and institutions in politics, government, business, technology, media, and civil society. Claiming to work with Chinese intelligence, military and security agencies, Zhenhua monitors the subject’s digital footprint across social media platforms, maintains an “information library,” which includes content not just from news sources, forums, but also from papers, patents, bidding documents, even positions of recruitment. Significantly, it builds a “relational database”, which records and describes associations between individuals, institutions, and information. Collecting such massive data and weaving in public or sentiment analysis around these targets, Zhenhua offers “threat intelligence services.”

Isn’t much of this publicly available data, so what’s the worry?

It is not data per se but the range and the use to which it may be put to that raises red flags. So Zhenhua’s 24 x 7 watch collects personal information on the target from all social media accounts; keeps track of the target’s friends and relationships; analyses posts, likes and comments by friends and followers; collects even private information about movements such as geographic location through Artificial Intelligence tools.

Domestic security agencies use such data for law and order applications such as tracking protests but in the hands of foreign agencies with no supervision or oversight, such data can serve a range of purposes. Seemingly innocuous granular information may be put together in a broader framework for deliberate tactical manoeuvring. That’s at the heart of what Zhenhua itself flaunts as its role in “hybrid warfare.”

So, what’s hybrid warfare?

As early as 1999, Unrestricted Warfare, a publication by China’s People’s Liberation Army, mapped the contours of hybrid warfare, a shift in the arena of violence from military to political, economic and technological. The new weapons in this war, wrote authors Colonel Qiao Liang and Colonel Wang Xiangsui, were those “closely linked to the lives of the common people.” And one morning “people will awake to discover with surprise that quite a few gentle and kind things have begun to have offensive and lethal characteristics.”

Indeed, within countries too, political parties target the opposition via these same tools.

“Every second country is giving hybrid warfare a shot since the Russian breakthrough in 2014-15 (annexation of Crimea and undeclared conflict in eastern Ukraine). But few match China’s capability as we have seen during the Hong Kong protests last year,” said a top cyber security expert.

Does this monitoring flout any laws in India?

Does this monitoring flout any laws in India?

Under the Information Technology Rules, 2011, under the IT Act, 2000, personal data is “any information regarding a natural person, which either directly or indirectly, in combination with other information available or likely to be available… is capable of identifying such person.” This, however, does not include information available freely or accessible in the public domain.

These rules also do not impose any conditions on the use of personal data for direct marketing etc. Many commercial entities access and aggregate such information for targeted advertisement. When it comes to third-party collection of data (like what Zhenhua does), it is slightly complicated. “The key point here,” said a data privacy expert who helped draft the new personal data protection Bill, “is that the company is undertaking this without consent… a third party scraping your geo-location from social media sites and sharing it with a rival country’s intelligence will be seen illegal, at least in some advanced jurisdictions.” But privacy laws are almost impossible to enforce in a foreign jurisdiction because they differ from country to country. That is unlikely to change anytime soon.

What’s the concern over Zhinhua’s monitoring?

As flare-ups intensified along the Line of Actual Control, India blocked, incrementally since June, over 100 Chinese apps for engaging in activities “prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order”. But such moves are unlikely to impact an operation like Zhenhua’s.

There have been a string of recent reports on China’s attempts to cultivate potential assets for sensitive military, intelligence or economic information in the US and Europe through social media.

There have been a string of recent reports on China’s attempts to cultivate potential assets for sensitive military, intelligence or economic information in the US and Europe through social media.

“Why does this company (Zhenhua) need processing centres in so many countries? If you don’t want attention from the platforms you are mass scraping, you simply use proxies,” said the Canberra-based expert Robert Potter who helped authenticate the data. “The only plausible purpose is to build capacity for following up on the actionable data.”

Zhenhua uses the open information environment liberal democracies take for granted to target individuals and institutions, said Potter. “The threat of surveillance and monitoring of foreign individuals by an authoritarian China is very real.”

Indian express